- Membership

- The NY Chapter

- Our Career Services

- Committees

- National FACC Network

Understanding CBDCs

February 24, 2021

Central Bank Digital Currency design points, issues, and predictions

By FACC Member, Carolyn Rogers

Program Director Business Automation, IBM

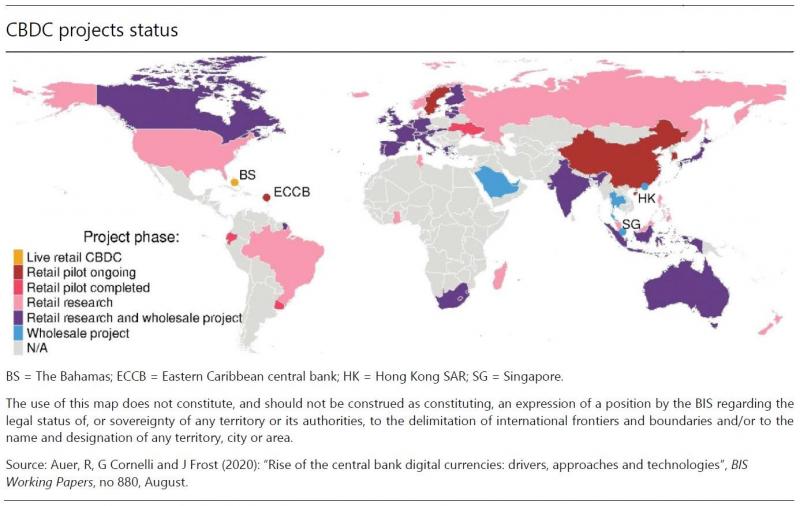

If you follow the world of crypto, DeFi, or the general landscape of blockchain-related initiatives, you probably started hearing more about Central Bank Digital Currencies, or CBDCs, in the past year. While study of the subject has been steadily growing for a while, 2020 saw a slew of new projects and exciting milestones like the arrival of the first “live” CBDC in the Bahamas. A new survey released just last week showed that 86% of Central Bank respondents had a CBDC initiative underway.

This momentum in experimentation is accompanied by momentum in the regulatory landscape as well, as the attitude of federal bodies seems to be shifting toward the possibility of CBDCs. In October 2020, seven major central banks collaborated on a CBDC “Hippocratic oath” of sorts, laying out principles for CBDC design. Earlier this month, the US Treasury’s Office of the Comptroller of Currency (OCC) issued a letter stating that banks can participate in node verification on a blockchain system, which effectively legitimizes blockchains as global financial networks.

While we are still in the early stages of CBDC development, we can start to imagine the impact they could have on the world. In preparation for what is sure to be a year filled with even more CBDC news, this article is meant to highlight the key design points, issues, and notable projects.

Defining Central Bank Digital Currency: Are we all talking about the same thing?

Somewhat. While understanding of the concept has progressed significantly through study and experimentation over the last few years, it remains relatively ill-defined because approaches can vary so widely. A 2018 paper attempted to describe CBDC according to what it is not: “a digital form of central bank money that is different from balances in traditional reserve or settlement accounts.” Generally speaking, the term refers to the collection of projects and proposals involving digital currencies issued by a central bank, inspired by “blockchain” — the technology framework whose first incarnation was Bitcoin. Depending on its design, such a currency could be available to the general public or not, interest-bearing or not, anonymous or not, or be secured with a blockchain or not. These choices would result in varying outcomes for an economy and a range of implications for consumers.

4 Key Design Points of CBDC

Ultimately, the success of CBDCs will depend on their design, and their design will depend on the economic profiles, consumer habits, and banking systems of their respective jurisdictions. This recent survey on CDBC progress around the world shows that projects differ starkly across countries in their economic and institutional motivations, policy approach, and technical design. These points affect whether the CBDC more closely resembles cash or bank deposits, how much they compete with existing payment mechanisms, and how accessible they are to consumers.

Design Point 1: Is it available to regular people or only banks?

In other words — is it “retail” or “wholesale”? The prevailing assumption is that an accessible, general purpose CBDC used by the public in day-to-day retail transactions would create more impact to existing systems than a wholesale CBDC accessible only to banks or a limited set of institutions. A retail CBDC would represent a cash-like claim on the central bank, and could even come to replace cash altogether. In countries like the near-cashless Sweden, where in 2020 less than 10% of payments were made in cash, this would simply be a continuation of a trend that was already well underway.

By contrast, a CBDC designed for wholesale use would not be as disruptive and could even closely resemble systems in place today (central banks already provide banks wholesale access to digital currency via reserves). Still, wholesale CBDCs could provide the additional benefit of settlement efficiencies especially when it comes to securities and derivatives. Overall, wholesale projects represent the minority of existing experiments compared to retail CBDC.

Design Point 2: Does it bear interest or not?

The extent to which a CBDC bears interest has a major effect on whether it most resembles cash or a bank deposit — and therefore what payment instrument it competes with most. The dynamics of a particular economy will determine how the general welfare is affected when either cash or bank deposits are threatened by the introduction of CBDC.

While many of the CBDCs currently under consideration are of a non interest-bearing type, this working paper from the IMF demonstrates that a non interest-bearing CDBC creates a challenging welfare tradeoff for the central bank. In short, a non interest-bearing CBDC creates an instrument that is cash-like, and in some circumstances would drive cash-usage down to zero. When access to cash and the preservation of payment variety is important to a society, this non-interest bearing approach may not be optimal.

This same analysis shows that a CBDC with a variable interest rate gives central banks the flexibility to create an optimal policy which “[sustains] variety in payment instruments and limits bank disintermediation.” Specifically, central banks can use a negative interest rate on CBDC to preserve the use of physical cash, and positive interest rates to affect demand for bank deposits. In a study on the effect of CBDCs on private banks, researchers showed that when a CBDC with positive interest rate is introduced, banks must raise their deposit rates to be at least equal to the CBDC, which creates more favorable conditions for depositors. The resulting increased demand for deposits may come from existing depositors encouraged to deposit more, but also from the unbanked now incentivized to pay the cost of accessing the banking sector. This positive effect on deposit rates and overall lending happens if the interest rate on CBDC is initially higher than deposits — but only up to a point. If the CBDC rate is too high and banks cannot respond, banks would be forced to scale down their deposits and loans.

Design point 3: How anonymous is it?

One of the benefits of cash is that it’s completely anonymous. That’s also one of the drawbacks. You can hold it, give it to someone, steal it, or lose it, and no one has to find out. CBDC can approach the anonymity of cash only when it takes a “token-based” approach, meaning that the digital currency is accessible through accounts or payment cards not tied directly to identity. Of course, this approach also suffers the cash-like vulnerability to loss and theft. Alternatively, an “account-based” approach to CBDC would make the currency available through an account at the central bank that can be accessed only with official identification — similar to the traceability of bank deposits.

But it doesn’t have to be either/or — a benefit of CBDC is that a blended approach is possible. For example, transactions could be recorded by the central bank but not accessed unless in specific circumstances (like when a transaction threshold is reached). Additionally, users’ identity could be shielded from various entities such as banks, law enforcement, or 3rd parties. The tradeoff between anonymity and security is crucial to adoption and the ultimate benefit to end-users. A 2020 analysis of the drivers and approaches to CBDC noted that account-based CBDCs relying on rigorous identity verification would likely exclude a core target group that already suffers exclusion from the traditional banking system — the unbanked and individuals who rely on cash.

Design point 4: Is the technology centralized or decentralized?

Asked another way — will the CBDC rely on conventional accounting technologies or will transactions be verified by multiple computers on a blockchain-like system? The end user may not experience much difference, but the technology choice could have implications around anonymity, security, and scalability. Blockchain or distributed ledger technologies (DLTs) could offer better resilience from single points of failure, placing trust in the underlying technology rather than in intermediaries or institutions. However, such systems would have to be carefully designed and are probably more advanced than most governments are prepared to implement and maintain. Unsurprisingly, most CBDC projects using DLT are focusing on “permissioned” approaches — that is, all the nodes participating in the verification of transactions on the network are known and admitted by some authority. This is in contrast to the “public” or “permissionless” networks that run cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin.

A note on related approaches: “Synthetic CBDC”

There is another proposed approach to CBDC called “synthetic CBDC” or “indirect CDBC.” It describes a hybrid approach in which e-money payment service providers act as an intermediary between the central bank and end users. This approach could have the benefit of creating a form of digital cash that is sanctioned by the central bank while being created and maintained by third party providers. Assuming the regulatory framework supports this approach, it could guarantee that these providers’ liabilities would always be fully matched by funds at the central bank. However, the recent joint paper by several major central banks makes it clear that they do not consider the synthetic approach to be true CBDC, because end users don’t actually have a claim on the central bank. They consider it a form of “narrow bank” money, which so far has seen unfavorable response from the Fed.

Why introduce CBDC?

CBDC interest is accelerating and exciting progress is being made in both mature and emerging markets. In addition to the issuance of the first live CBDC in the Bahamas, 2020 saw 60% of central banks working on proofs-of-concept and 14% moving into pilot phases. While most central banks are unlikely to issue CBDC in the near future, a group of banks representing a fifth of the world’s population say they are likely to issue CBDC in the next three years.

In general, local circumstances shape the impetus for CBDC work but there are some common motivations. One is payment efficiency, both in domestic and foreign transactions. Another is financial inclusion, but as noted earlier, this would depend on key design choices. For example, financial inclusion may depend on whether the competitive pressure of CBDC actually causes banks to increase their deposit interest rates to a level that would incentivize the unbanked to access the banking sector. It may also depend on the level of identification required to access a central bank account. A third motivation for CBDC is better control and implementation of monetary policy. A widely used and held CBDC could be used as a tool to transmit monetary policy directly to households, like executing “helicopter drops” in times of financial stress. Additionally, it is generally thought that a CBDC would be cheaper to implement and maintain in the long-run than minting physical coins and bills.

On the other hand, there is no guarantee that a CBDC will work as intended. A fundamental question to ask is: does it make sense for a central bank to run internet money? Many who have been working for years in the crypto and DeFi space, striving to build open, free, and fair financial markets, balk at the idea of a monopolized, centrally run digital currency that could augment the control of the federal government. It seems antithetical to the original purpose of the space — to facilitate peer to peer, decentralized transactions without relying on traditional institutions. This kind of unease is palpable in discussions of China’s plans for its digital yuan, which is expected to “strengthen its digital authoritarianism.”

Predictions for the year ahead

You’ll probably hear a lot more about CBDCs in 2021. China has successfully concluded its second pilot program and seems to be gearing up for a mass rollout. Sweden’s e-krona pilot project, launched in early 2020, is set to wrap up this month. The Eastern Caribbean Central Bank, hot on the heels of the Bahamas Sand Dollar, is readying its digital currency for production. These early movers will surely be closely watched for the results and lessons they provide.

While most central banks are not expected to issue a CBDC any time soon, the progress in this space is part of larger movement that goes beyond the question of whether or not governments should issue digital currency. In tandem with continued momentum in crypto and DeFi, the bigger question is — what is the best combination of payment systems to support the modern economy? It’s no coincidence that Bitcoin continues to surprise people and major banks are positioning themselves to be more crypto-friendly. By all indications, we’re in for an exciting year ahead.

See here the orignal publication.